PALIMPSESTS

Of Sonorous Medieval Chinese Texts and NLP Model Training

A distinctive set of challenges arises when training machines to process a historical language, especially one that was last spoken two millennia ago. One of the core issues embedded in natural language processing (NLP) models for historical languages is the acute lack of annotated datasets, despite the long scholastic and exegetical traditions for some of these languages. This article focuses on a specific historical language with an extensive commentarial tradition: premodern forms of Chinese spanning the Warring States (476–221 BCE) and early imperial (221 BCE–220 CE) periods. By highlighting the challenges of this particular language and our approach to building an NLP model that aims to overcome these difficulties, we will argue how textual commentaries from the medieval period can be used for NLP model training purposes.

It may at first appear that the goal of an NLP model for historical languages consists in building the largest model and extracting the highest accuracy score from it. Conventional wisdom holds that larger is better when it comes to datasets, particularly for modern languages, in order to build a seemingly complete picture of the target language.1 It may be equally tempting to rely on the currently dominant focus in NLP by building contextual representations of meaning in the form of word embeddings. (This is nowhere more apparent than in the currently ubiquitous assertion that “attention is all you need” in the Transformer architecture.2)

But when approaching a language like Old Chinese, the architecture and hyperparameters3 of the model itself are, at best, of secondary concern. In reality, the bulk of time and effort is devoted to questions of data curation and the painstaking labor necessary to identify and annotate the unique qualities of this language.4 As we will see, the question of meaning in context is far more complex than counting the collection of words surrounding the one we happen to be interested in, as the Transformer architecture would imply. Additional considerations include questions like: Who will curate the corpus of texts? How will this corpus be made machine readable? What portions will be used for the training and evaluation of the model?

In the project we introduce here5 — the result of a collaboration between a software engineer and a philologist — we generate an NLP model based on data derived from premodern Chinese annotations. In many ways, we have found that questions facing the twenty-first-century researcher equipped with large language models and Python libraries echo those of the sixth-century scholar using brush and ink.

I.

Let’s begin by describing some of the distinctive features of Old Chinese, a language that survives in a corpus of ancient texts that can be dated to the centuries preceding and during the first dynasties of Imperial China, or roughly 476 BCE to 220 CE. These written texts survive either as documents that were transmitted and copied through the millennia, or as recently excavated or otherwise surfaced manuscripts.6

Figure 1. Four Wooden Tablets in clerical script, Freer Gallery of Art (accessed August 20, 2023). Figure 1. Four Wooden Tablets in clerical script, Freer Gallery of Art (accessed August 20, 2023). The online version of this essay includes an interactive deep zoom viewer displaying a high resolution version of this image.

For heuristic purposes, we use the term “Old Chinese” for the underlying language, and like other stages of the Chinese language family, it is marked by the usage of Chinese characters or glyphs. As a writing system, Chinese glyphs have remained largely stable from the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) to the present day, with the greatest change occurring in 1956 in the form of the People’s Republic of China’s script reform and the introduction of simplified characters. A text from the early twentieth century may thus on the surface appear indistinguishable from a genuinely ancient piece of writing. This is in particular the case due to the venerated status of a few classical texts, largely from pre-imperial China, which served as models for later literary forms of writing up until the twentieth century. Existing NLP models for premodern Chinese assume a seemingly enduring and unchanging use of the written language, grouped under the notions of “Literary” or “Classical Chinese” (wen yan 文言 and gudian Hanyu 古典漢語).7 But this understanding of a never-changing and static language is not just ahistorical and incorrect; it also misses the point of what Chinese glyphs inherently represent: like other forms of writing, they are a conventionalized system used to represent the dynamic utterances of a language.

In this sense, sound is crucial to reading early Chinese texts, and the content of these texts is often inextricably linked to the topic of sound: the Chinese classics and texts of the genre of Masters literature (zi shu 子書) are astoundingly rich in puns, rhymes, and wordplay.8

Often, these texts present themselves as representing speech, and many of them may have had performative functions and poetic features that remain largely hidden, simply due to the fact that the Chinese writing system only poorly reflects its phonological features.9 The conceit of continuous access to written heritage is thus a mirage.

The sound system of the language underwent significant changes even as its graphemes remained static.

So how can we access the sounds of a language that lost its last native speakers millennia ago? Chinese — like other languages — has changed over time. More specifically, the sound system of the language underwent significant changes even as its graphemes remained static. Old Chinese phonology is therefore a reconstructed system, derived from documentary evidence. In this context, heteronyms pose an issue also present in modern forms of Chinese: characters whose pronunciation and meaning change based on context, defying attempts to convert them directly into phonemes.10 One of the best-known examples of such a homograph is the glyph 樂, which can be read — depending on context — as either lè (“joy”) or yuè (“music”) in modern Standard Chinese, which can be reconstructed as *[rˤ]awk or *[ŋ]ˤrawk in Old Chinese.

| Old Chinese | US English | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 樂 | excuse | |||

| meaning | music | joy | to forgive | justification |

| sound | *[ŋ]ˤrawk | *[r]ˤawk | /ɪksˈkjuz/ | /ɪksˈkjus/ |

Another problem is the graphic variation common in early forms of Chinese, especially prior to the large-scale standardization of orthography during the third to first centuries BCE. In other words, while one glyph could be pronounced multiple ways, the same word could additionally be written with different glyphs in ancient texts. The same textual passage — say, a line of a poem — could hence be written with rather different glyphs.11 Thus without a model that incorporates homographs, graphic variation, and other contextual understandings of phonology, the (often quite complex) puns, rhymes, and wordplays of ancient texts remain hidden below their surface forms. More crucially, however, unstandardized recurrences — not just of named entities, but of entire parallel passages — may go unnoticed.12

Figure 3. Textual parallels across three early Chinese texts, both on a grapheme level and on that of phonology alone. The phrase “he did not speak for three years” (solid underline) occurs across these texts, using the same glyphs. Passages with wavy and dotted underlines utilize different glyphs, but largely overlap on a phonological level.

For these examples, see David Schaberg, “Speaking of Documents: Shu Citations in Warring States Texts,” in Origins of Chinese Political Philosophy: Studies in the Composition and Thought of the ‘Shangshu’ (Classic of Documents), ed. Martin Kern and Dirk Meyer (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 320–59.

作其即位,乃或亮陰,三年不言。其惟不言,言乃雍。

At the start, when he ascended the throne, then, it is said, the light was obscured and for three years he did not speak. His acting without words was thus harmonious.

書云:高宗三年不言,言乃歡。

The Documents state: ‘Gaozong did not speak for three years. When he did speak, he was joyous.’

高宗,天子也。即位諒闇,三年不言。

Gaozong was Heaven’s Son. When he ascended the throne, it was truly dark, and for three years he did not speak.

Fortunately, previous scholarship has grappled with many of these issues, and historical secondary sources offer an intriguing source of semi-structured data in the form of commentaries, dictionaries, and other scholarly work. The Qieyun 切韻, a rhyme dictionary compiled in 601 CE, is an important example: it records normative reading practices that represent a compromise between then-current Northern and Southern styles of pronouncing of glyphs in the classical texts from early China. Modern reconstructions of Old Chinese phonology draw heavily on the Qieyun and its later redactions, as these texts provide a formal structure and closed system of phonological distinctions for the underlying Middle Chinese.

The often quite complex puns, rhymes, and wordplays of ancient texts remain hidden below their surface forms.

The stability of the script also led to problems over time. In China, generations of medieval and early modern writers were trained to memorize the Odes of the ancient Shi jing 詩經 — called the Classic of Poetry for a good reason — but they soon grappled with the fact that these texts largely did not to rhyme when read aloud. The underlying phonology had changed.13

Figure 4. Selected lines of the poem “Guan ju” 《關雎》 from the Classic of Poetry (Shi jing 詩經), expressed through glyphs, Old Chinese and Middle Chinese phonology, and the pinyin romanization system of Standard Mandarin Chinese. Rhyming words are underlined with their matching vowel sounds glowing; note in particular the disappearing rhymes in selection 1 from Middle Chinese to Modern Chinese, and in selection 2 from Old Chinese to Middle Chinese.

| Old Chinese | Middle Chinese | Modern Chinese | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 關 | *kʕro[n] | kwaen | guān |

| 關 | *kʕro[n] | kwaen | guān |

| 雎 | *[tsh]a | tshjo | jū |

| 鳩 | *[k](r)u | kjuw | jiū |

| 在 | *[dz]ʕәʔ | dzojX | zài |

| 河 | *[C.g]ʕaj | ha | hé |

| 之 | *tә | tsyi | zhī |

| 洲 | *tu | tsyuw | zhōu |

| Old Chinese | Middle Chinese | Modern Chinese | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 求 | *g(r)u | gjuw | qiú |

| 之 | *tә | tsyi | zhī |

| 不 | *pə | pjuw | bù |

| 得 | *tʕәk | tok | dé |

| 寤 | *ŋʕa-s | nguH | wù |

| 寐 | *mi[t]-s | mjijH | mèi |

| 思 | *[s]ə | si | sī |

| 服 | *[b]ək | bjuwk | fú |

II.

Instead of annotating early Chinese texts manually to disambiguate these problems in reading a given passage, we decided to rely entirely on traditional Chinese scholarship on the ancient classics as a data source. In order for such premodern scholarship to be fruitfully utilized as a data source for NLP training purposes, and for such scholarship to address the problem of disambiguating different readings, several criteria must be met. Initially, the source text must provide phonological data as explicitly as possible — after all, our aim is to assemble a language model that meaningfully reflects not just the glyphs used, but also their underlying sounds. Secondly, older scholarly sources are better; however, unlike Middle Chinese, which offers a convenient textual starting point in the form of the Qieyun, approaching Old Chinese inevitably includes Middle Chinese data, given the significantly closer temporal proximity of medieval scholars — like the Qieyun’s compilator Lu Fayan 陸法言 (ca. 581–618) — to the ancient classics. Thirdly, data is needed on pronunciations given in realistic contexts in order to overcome the problems of homographs and graphic variation. That way, a future model of ours can use this contextual information to improve its accuracy.

One early work appears to fulfill all of these criteria: the Jingdian Shiwen 經典釋文, completed in 583 CE by the scholar Lu Deming 陸德明 (d. 630). This monumental commentary provides tens of thousands of phonological, semantic, and bibliographic notes across a representative selection of sixteen ancient classical texts. The material being annotated is broad, ranging from poetic odes (the Shi jing) and historical chronicles (the Chunqiu 春秋 and its commentaries) to an ancient dictionary (the Erya 爾雅). Lu Deming’s analysis draws from some 230 sources, some of which are not attested in any other work.14

Lu Deming’s meticulous attention to detail produced what is effectively a machine-readable dataset millennia before such machines would exist.

The Jingdian Shiwen wrestles with some of the same problems we face today, as its commentarial style disambiguates homographs and the inconsistencies presented by graphic variation in the texts it studies. While Lu Deming lived during a tumultuous period that spanned multiple imperial dynasties and spawned many competing schools of thought on how the classics should be read, his explanatory annotations eventually received official recognition and earned him posthumous fame and a commendation from emperor Taizong 太宗 (598–649) of the Tang dynasty 唐 (618–907 CE).15

The Jingdian Shiwen utilizes a relatively novel form of commentary: rather than reproducing the source text in full, it instead lists only what we call headwords, which are short excerpts, ranging from single glyphs to short passages. Each of these short sequences of glyphs is paired with a corresponding annotation. Each headword is distinctive enough to be matched to its location in the full text of the original source. The Jingdian Shiwen is thus a semi-structured text that provides sequences of glyphs that can be located in specific contexts in the source texts, and supplies annotations for a specific glyph in the relevant sequence.16 By essentially compressing the source texts in this way, the Jingdian Shiwen manages to cover almost 900,000 characters of primary-source material in just over 100,000 characters of excerpt. The resulting “compression ratio” is 13:1.17

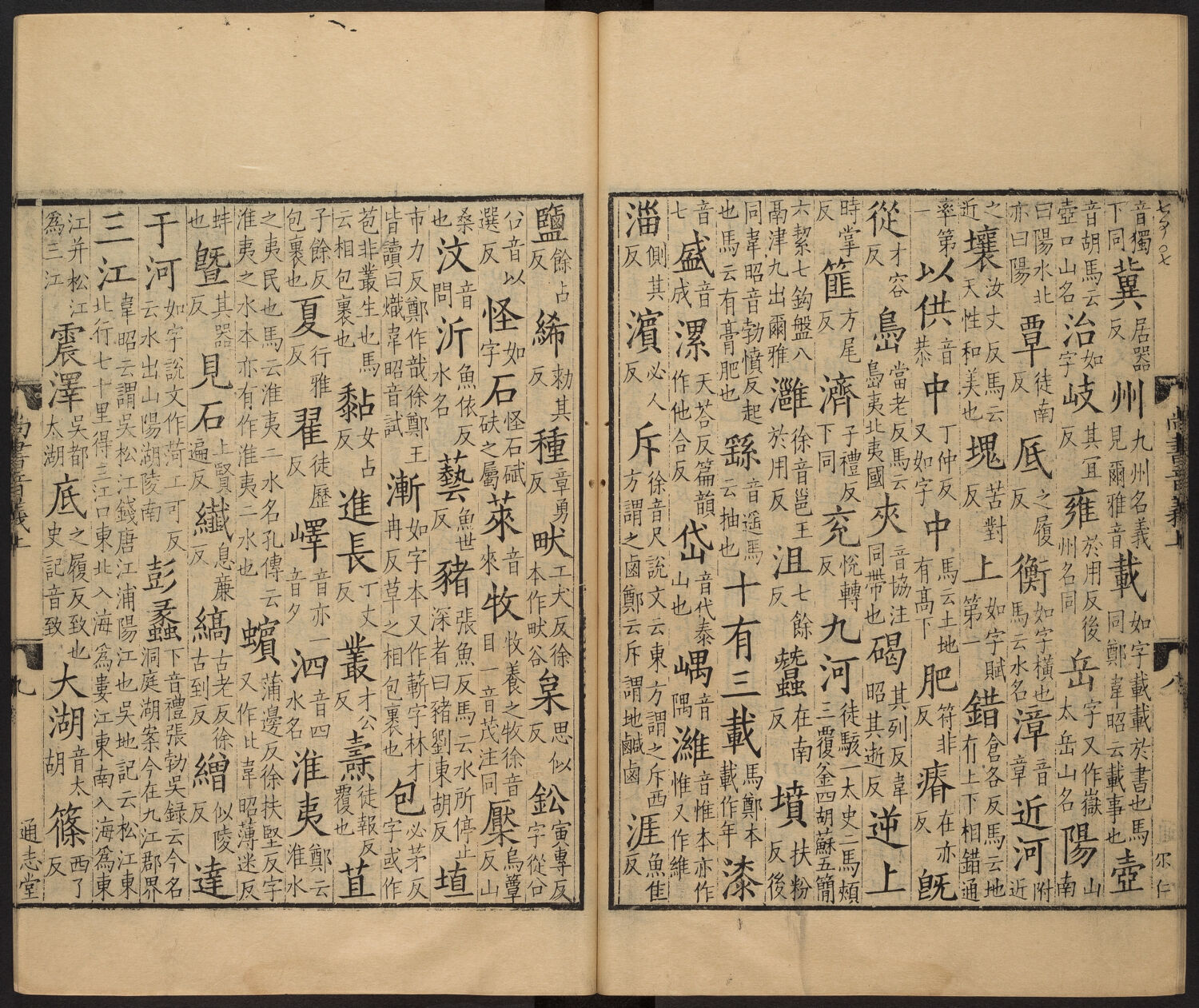

Figure 5. Folio from 1680 printing of the Jingdian Shiwen, with headwords rendered in large glyphs, and annotations immediately following in half-width running in two columns; from Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University (accessed September 3, 2023) Figure 5. Folio from 1680 printing of the Jingdian Shiwen, with headwords rendered in large glyphs, and annotations immediately following in half-width running in two columns; from Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University (accessed September 3, 2023) The online version of this essay includes an interactive deep zoom viewer displaying a high resolution version of this image.

While earlier dictionaries primarily glossed glyphs by providing similar-sounding glyphs to indicate their reading, the Jingdian Shiwen employed a rather novel way of indicating pronunciation: the fanqie 反切 system.18 This method of noting a glyph’s phonology separates a syllable into its initial consonant on the one hand, and its rhyme and tone on the other. No longer constrained to providing pronunciations by finding a word that overlapped exactly in sound, the fanqie system allowed scholars such as Lu Deming to instead choose common graphs for the initial and rhyme plus tone independently. Given the reliance on the Chinese script, both initial and rhyme plus tone are expressed through a common glyph.

Figure 6. How the fanqie pronunciation system works

In this way, the Jingdian Shiwen is both comprehensive and concise in the way it provides phonological data in context. We believe it provides enough data to train an NLP model. The key question is then how to extract this data; while Lu Deming’s meticulous attention to detail produced what is effectively a machine-readable dataset millennia before such machines would exist, adjusting the specific format still necessitates significant labor on our part.

III.

The first obstacle we face in turning the Jingdian Shiwen into phonological training data is the need for a digitized version of this text. Fortunately, the Kanseki Repository, an online database of premodern Chinese texts, offers digitized editions of over nine thousand works, including the Jingdian Shiwen and the source texts it annotates.19 This repository usually offers multiple editions for each work, in addition to interpretive versions that attempt to merge the editions into a state-of-the-art copy of the text. In keeping with the repository’s permissive licensing and spirit of “electronic texts by researchers, for researchers,” our own work is available under an open license and published on GitHub.20

Only with such a digitized version of the Jingdian Shiwen and related texts can we approach the key question of how to extract useful phonological data from Lu Deming’s commentary. A look at the content of this text highlights why this question is crucial: while close to one-third of the roughly 55,000 notes in the Jingdian Shiwen consist solely of a reading gloss (thus providing a reading aid to indicate pronunciation), the remainder is more complex and addresses multiple concerns. Some annotations feature semantic glosses, and others highlight instances in which additional works reproduce a glyph differently or include citations to the interpretations of other scholars. Many annotations combine these different elements. More importantly, the Jingdian Shiwen contains yet another form of abridgement: instead of reproducing the same annotation multiple times, the text attaches qualifiers to indicate that a given reading applies every time a human reader encounters the given string of glyphs in a specific section of the source text. These qualifiers act as multipliers for the data, effectively extending the commentary to cover whole swaths of text not explicitly noted elsewhere.

Figure 7. An example showing the richness of annotations in the Jingdian Shiwen 經典釋文, and the common patterns they take.

相摩

本又作磨

末何反

京

云相磑切也

磑音古代反

馬

云摩切也

鄭

注禮記

云迫也

迫音百

Our approach to handling these complexities is to train a special-purpose model equipped to parse the terse style of the Jingdian Shiwen’s highly structured annotations. We use the Prodigy annotation tool to note parts of speech and syntactic relationships in the commentary, and pair it with the spaCy NLP library to create a custom processing pipeline.21 By applying this micro-model to the annotation corpus, each individual reading gloss can be extracted and paired with qualifying data. A notable side effect of this approach is that it simultaneously produces a citation network dataset: references that the Jingdian Shiwen makes to other texts and authors can be extracted from the text along with phonological data.

Once we have extracted all of the relevant phonological data, the task still remains to transform it into reconstructed forms of first Middle Chinese, and then Old Chinese. This is a process involving a few considerations: while the reading glosses of the Jingdian Shiwen — given directly and in fanqie form — reflect Middle Chinese, these glosses can also be used to make some inferences about the earlier Old Chinese. In order to strengthen these inferences, we use the reading glosses provided by the Jingdian Shiwen as disambiguation data and cross-reference these glosses with both contemporary rhyme dictionaries like the Qieyun and modern historical linguistic data (primarily William H. Baxter and Laurent Sagart’s 2014 reconstruction of Old Chinese22). The overall goal is to stay as true as possible to the source material: if the rhyming portion of a syllable can be determined, but its initial consonant is represented ambiguously in the Jingdian Shiwen, we attempt to capture that ambiguity in the data.

We borrow a strategy from the modern science of bioinformatics: specifically, genetic algorithms designed to find the best overall “alignment” of sequences of amino acids (or, in our case, sequences of glyphs).

Finally, in order to create a fully machine-readable dataset, we reunite the annotations of the Jingdian Shiwen with the full text of the classical works that it annotates. Because of the Jingdian Shiwen’s tendency to economize on space by attaching comments to excerpted headwords, identifying the precise locations in the text where the headwords occur is necessary to match the annotations to their original context. To do this, we borrow a strategy from the modern science of bioinformatics: specifically, genetic algorithms designed to find the best overall “alignment” of sequences of amino acids (or, in our case, sequences of glyphs).23 Once the headwords have been matched to their original positions in the source text, we copy over their corresponding phonological data to obtain a dataset of reading glosses in their historical context.

In using historical secondary sources for training an NLP model, we have found that even sources compiled millennia ago can still be considered by their very nature semi-structured data of the type needed to construct a model. The constrained, formulaic syntax of dictionaries and commentaries — an unnatural language designed to be quickly parsed by a human reader — lends itself equally well to parsing by relatively simple algorithms. For historical languages, secondary sources may even form a substantial part of the entire known body of the language, providing invaluable contemporary context to their literary counterparts.

Our project continues the practice of reading classical texts as data, but with a different aim than previous iterations of this practice: our goal is to produce a machine-learning algorithm. Some of the outlined steps that we have used to parse the Jingdian Shiwen are still works in progress, and additionally, some of the most difficult work remains to be approached. Constructing a statistical model that can represent all the complexities of current hypotheses regarding Old Chinese syllables will strain the limits of contemporary NLP platforms, most of which have no concept whatsoever of phonology. Our aim here is to persuade our peers that this task, and others like it in other languages, is not just possible but wholly worthwhile for researchers in the humanities. For this reason, we believe that further collaboration — with digital humanists, philologists, and others interested in expanding the debates around ancient texts to incorporate sound — is one of the most generative approaches to making use of NLP frameworks in the study of ancient texts.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible through our participation in the “New Languages for NLP: Building Linguistic Diversity in the Digital Humanities,” a National Endowment for Humanities Institute for Advanced Topics in the Digital Humanities. Our thanks to the organizers, Natalia Ermolaev and Andrew Janco, and to Toma Tasovac, Quinn Dombrowski, and David Lassner. We also thank Gissoo Doroudian and Rebecca Sutton Koeser for their design and implementation of the figures of this article, in a lively exchange with Nick Budak. Figure 4 was further based on the work of Jeffrey R. Tharsen, whose work more generally has inspired many of the thoughts in this article. Lastly, thank you to Grant Wythoff for his erudite editorial work.

Compare, however, the danger of this tendency, as shown by Emily M. Bender et al., “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜,” FAccT ‘21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2021), 610–23, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922. ↩︎

This phrase is referring to the idea that in order to get a sense of the meaning of a target word, one need only carefully to select from among its surrounding context words; it draws from the title of Ashish Vaswani et al., “Attention Is All You Need,” NIPS'17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (Red Hook: Curran Associates, 2017): 6000–10, https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf. “Attention” refers specifically to an algorithmic method of calculating the importance of context words relative to the target. ↩︎

Because large language models are, in effect, collections of billions or even trillions of individual weights or parameters, this term is used to refer to the meta-values that are used to configure and train the model itself. ↩︎

Compare, in this context, insights from Toma Tasovac et al., “Humanistic NLP: Bridging the Gap Between Digital Humanities and Natural Language Processing” (paper, Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations Conference, Graz, Austria, July 13, 2023). ↩︎

Nick Budak and Gian Duri Rominger, “DIRECT: Digital Intertextual Resonances in Early Chinese Texts,” GitHub, last modified August 17, 2023, https://github.com/direct-phonology. ↩︎

Besides manuscripts stemming from archaeologically excavated sites, numerous looted manuscripts have surfaced in the last few decades. For issues regarding this trend, compare Paul R. Goldin, “Heng Xian and the Problems of Studying Looted Artifacts,” Dao 12 (2013): 153–60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-013-9323-4; compare also Goldin’s response to his critics in “The Problem of Looted Artifacts in Chinese Studies: A Rejoinder to Critics,” Dao 22 (2023): 145–51, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-022-09870-8. ↩︎

Compare, for example, “SuPar-Kanbun,” a BERT model trained on Classical texts; see Koichi Yasuoka et al, “Designing Universal Dependencies for Classical Chinese and Its Application.” Journal of Information Processing Society of Japan 63, no. 2 (2022): 355–63, http://id.nii.ac.jp/1001/00216242/. In such models, the target language is often simply defined in opposition to modern Standard Chinese, and the training data consists of texts from across the millennia. ↩︎

Pronunciation data, often rendered in the International Phonetic Alphabet, is at best noise and at worst misinformation for Transformer models; the significance of a newspaper headline like the Washington Post’s description of Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz’s 2020 campaign as being in “a whole latte trouble” would be completely lost. See Dana Milbank, “Howard Schultz Brings a Whole Latte Trouble,” Washington Post, January 30, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/howard-schultz-brings-a-whole-latte-trouble/2019/01/30/6d45a1ee-24cb-11e9-ad53-824486280311_story.html. For an overview of the so-called Masters literature (zi shu) and issues within this genre, compare, for example, Wiebke Denecke, The Dynamics of Masters Literature: Early Chinese Thought From Confucius to Han Feizi (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010). For the importance of sound in texts, compare, for example, Wolfgang Behr, “Three Sound-Correlated Text Structuring Devices in Pre-Qín Philosophical Prose,” Bochumer Jahrbuch zur Ostasienforschung 29 (2005): 15–33, https://zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/113766/. For discussions of the transformative effects of sounds, music, and poetry, see Haun Saussy, The Problem of a Chinese Aesthetic (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), 77–105; and Steven Van Zoeren, Poetry and Personality. Reading, Exegesis, and Hermeneutics in Traditional China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991), 95–103. On the relationship between music and rulership in early China and its assumed cultivating effects, see especially Kenneth J. DeWoskin, A Song for One or Two. Music and the Concept of Art in Early China (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Center for Chinese Studies; Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies no. 42, 1982), 13–14, 85–98. ↩︎

Compare, for example, Martin Kern, “Creating a Book and Performing It: The ‘Yao lüe’ Chapter of the Huainanzi as a Western Han Fu,” in The Huainanzi and Textual Production in Early China, ed. Sarah A. Queen and Michael Puett (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 124–50. ↩︎

See Frederick Liu, Han Lu, and Graham Neubig, “Handling Homographs in Neural Machine Translation,” in Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, vol. 1 (New Orleans: Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018), 1336–45, https://aclanthology.org/N18-1121. ↩︎

Compare, for example, Martin Kern, “The Odes in Excavated Manuscripts,” in Text and Ritual in Early China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005), 149–193, esp. 171. For broader overviews of the developments of Chinese writing in antiquity, compare Xigui Qiu, Gilbert Louis Mattos, and Jerry Norman, Chinese Writing (Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, 2000); William G. Boltz, The Origin and the Development of the Chinese Writing System (New Haven: American Oriental Society, 2003); and Imre Galambos, Orthography of Early Chinese Writing: Evidence from Newly Excavated Manuscripts (Budapest: Department of East Asian Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, 2006). ↩︎

Compare David Schaberg, “Speaking of Documents: Shu Citations in Warring States Texts,” in Origins of Chinese Political Philosophy, ed. Martin Kern and Dirk Meyer (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 320–59. Compare also recent arguments regarding the applicability of the concept of mouvance to early Chinese textual phenomena; see Martin Kern, “‘Xi Shuai’ 蟋蟀 (‘Cricket’) and Its Consequences: Issues in Early Chinese Poetry and Textual Studies,” Early China 42 (2019): 39–74, esp. 56–62, https://doi.org/10.1017/eac.2019.1; compare also Dirk Meyer, Documentation and Argument in Early China: The Shangshu (Venerated Documents) and the Shu Traditions (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2021), 17–19. ↩︎

For the underlying logic of representing early Chinese texts through visualizations of their phonological features, and for a fuller aural representation of the poem “Guan ju” upon which figure 4 is largely based, see Jeffrey R. Tharsen, “From Form to Sound 自形至聲: Visual and Aural Representations of Premodern Chinese Phonology and Phonorhetoric with Applications for Phonetic Scripts.” International Journal of Digit Humanities 4 (2023), 115–129, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42803-022-00053-8. Further note that the Ming dynasty scholar Chen Di 陳第 (1541–1617) used this problem of the Odes not rhyming to persuasively make the case that the Chinese language had undergone significant phonological change since ancient times; see William H. Baxter, A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology (Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, 1992), 154–55. ↩︎

For more background on different premodern Chinese lexicons, compare Zev Handel, “Early Lexicons,” in Literary Information in China: A History, ed. Jack W. Chen et al., (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021), 53–64, esp. 60–61 for the Qieyun and sound-based lexicons; and also Victor H. Mair, “Tzu-shu 字書 or tzu-tien 字典 [Dictionaries],” in The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature, ed. William H. Nienhauser, vol. 2 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998); for more on the Jingdian Shiwen, see David B. Honey, Northern and Southern Dynasties, Sui, and Early Tang: The Decline of Factual Philology and the Rise of Speculative Hermeneutics, vol. 3 of A History of Classical Chinese Scholarship (Washington: Academica Press, 2021), 215–20. ↩︎

See David B. Honey’s translation of Lu Deming’s biography from the New Tang History (Xin Tang shu 新唐書) in Decline of Factual Philology, 216–19. ↩︎

The use of the Jingdian Shiwen as a data source was pioneered by Jeffrey R. Tharsen and Hantao Wang, who categorized and segmented the Jingdian Shiwen systematically as a database; see Jeffrey R. Tharsen and Hantao Wang, “Digitizing the Jingdian Shiwen《經典釋文》: Deriving a Lexical Database from Ancient Glosses” (poster, Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities and Computer Science (DHCS), University of Chicago, USA, November 14, 2015. https://doi.org/10.6082/uchicago.8367); see also Jeffrey R. Tharsen, “Understanding the Databases of Premodern China: Harnessing the Potential of Textual Corpora as Digital Data Sources” (paper, Digital Research in East Asian Studies: Corpora, Methods, and Challenges Conference, Leiden University, the Netherlands, July 12, 2016. https://doi.org/10.6082/uchicago.8368). We were initially unaware of the work of Tharsen and Wang, and at first approached the Jingdian Shiwen purely from the needs of training a Natural Language Processing model. Our approach therefore utilizes a different labeling schema that was focused on the NLP model training, and a different digitized version of the source text. Nonetheless, we are grateful for Tharsen and Wang for generously sharing their data, which allowed us to compare their data and approach to ours. As part of our approach, we understand the Jingdian Shiwen as a dictionary, and we identify its semi-structured dictionary form also as the reason why an approach relying solely on the Transformer architecture would be misleading. Compare this to the ability of a human reader who speaks English to look up any word she may find in a source text in the Oxford English Dictionary. GPT-3 processes the same text differently, and the only way it learns from the dictionary as a text is in the same way it understands a sequential text like Moby-Dick. ↩︎

For comparison, in terms of file size, the modern “gzip” algorithm compresses the entirety of the same corpus with a ratio of about 3:1. ↩︎

This more abstract understanding of phonology may have reached Chinese scholars by way of Sanskrit and Indian linguistics, which had gained relevance with the increasing institutionalization of Chinese Buddhism in the sixth and seventh centuries; compare Mair, “Tzu-shu 字書,” 168. ↩︎

“About Kanseki Repository,” Kanripo, last accessed August 21, 2023, https://www.kanripo.org/. ↩︎

Nick Budak and Gian Duri Rominger, “DIRECT: Digital Intertextual Resonances in Early Chinese Texts,” GitHub, last modified August 17, 2023, https://github.com/direct-phonology. ↩︎

For the Prodigy annotation tool, see “Prodigy 101 — Everything You Need to Know,” Prodigy, accessed August 12, 2023, https://prodi.gy/docs. For spaCy, see “spaCy 101: Everything You Need to Know,” spaCy, accessed August 21, 2023, https://spacy.io/usage/spacy-101. ↩︎

For this reconstruction, see William H. Baxter and Laurent Sagart, Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199945375.001.0001. ↩︎

For an example of this technique as applied to finding quoted passages in Chinese text, compare Paul Vierthaler and Mees Gelein, “A BLAST-Based, Language-Agnostic Text Reuse Algorithm with a MARKUS Implementation and Sequence Alignment Optimized for Large Chinese Corpora,” Journal of Cultural Analytics 4, no. 2 (2019), https://doi.org/10.22148/16.034; this inspired our dphon tool. ↩︎