PROCESSES

Casting in Reverse: Recuperating Sixteenth-Century Marks and Makers through Data Curation and 3D Imaging

In 1611, German ducal agent and art collector Philipp Hainhofer recorded two bronze statuettes in an imperial Augsburg collection: “a group of a lion slaying a horse,” and “a group of a lion slaying a bull.” These sculptures, he writes, were “di mano del” (by the hand of) Florentine court sculptor, Giambologna (1529–1608).1 From Giambologna’s eighteenth-century biographer, we learn that the subjects were cast in multiple, continuing even after his death.2 Though the location of the Augsburg casts is unknown, others survive across various collections. Only two “sets,” however, are signed, one in the Galleria Corsini in Rome and the other broken up between the Louvre and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Figure 1. Antonio Susini; after Giovanni da Bologna, Lion Attacking Horse, ca. between 1580 and 1590, bronze, red lacquer.Detroit Institute of Arts, City of Detroit Purchase, 25.20.

And yet, it is not Giambologna’s name that we find etched into them; instead, on the horse reads “ANT. SVSI/INI OPVS/FLORE.,” and the bull “ANT./SVSINI/F.”—that is, on one, “the work of Antonio Susini, Florentine”; on the other, “Antonio Susini made this.”3

For about twenty years, from 1581 until around 1600, Antonio Susini (1558–1624) worked for Giambologna as his assistant and collaborator. As Giambologna’s reputation working for the Medicean court grew, so too did his market and, by extension, his workshop. Working between marble and bronze, large and small scales, Giambologna employed several assistants across media and specialties. Though Susini assisted with the colossal bronzes, he was primarily responsible for carrying out small-scale bronze copies and reductions after Giambologna’s designs. Whether beginning with a large-scale marble, a clay model, or a prefabricated mold, Susini would produce an intermediary model in wax, which he, put simply, would then refine, cast, and finish. Giambolognan in design and authorship, these works were Susini-made. For Susini to sign the Lion Attacking a Bull with an “F” for “fecit,” or “made,” is on some level to acknowledge these divisions—and slippages—in labor and media. It is to state outright his role as executor, a distinction that has the added effect of distancing himself from designer. The opposite seems at play in his use of “opus” for Lion Attacking a Horse. Based on an antique prototype in marble, then still fragmented, this work is thought to be an experimental reconstruction in bronze, which Susini’s choice signature takes credit for. Scholarship is uncommitted to this latter construction, seeing Susini’s interventions as not necessarily autonomous; whatever the case, and “by the hand of” Giambologna or not, these works are perpetually inscribed by the Susini name.4

Artists moved from model, to wax, to bronze. My data sculpts in reverse, moving from bronze cast, to maker, and eventually, the lost model.

While contemporaneous accounts depict Susini as more of a promising protégé than an anonymous middleman, scholarship over the subsequent centuries tends only to value assistants and pupils when they are seen to surpass their teacher—a fate Susini, ostensibly, did not meet. Over the years, scholarship has simultaneously labeled him a “superior craftsman” and an “absolutely uncreative manufacturer” who, “so long as he stayed in Giovanni Bologna’s studio, was neither a full-fledged technician nor sculptor.”5 When Susini is remembered, it is as the harbinger of a particular style or finish in bronze—he brought to the genre of small-scale bronzes heightened polish, refined chasing, and a characteristically angular treatment of forms. Giambologna himself would regard Susini’s casts as “the most beautiful things that they [patrons] can have from my hands,” seeing the latter’s labor, technical acumen, and, even, body as surrogates for his own.6 Indeed, to speak of “a Susini” bronze today is to directly comment upon a work’s execution and finish; in a twist of phrase, his name has come to signify just as much a technical faculty as it does a person.

In the field of Renaissance art where the primacy of design and the “Idea” reign, to prioritize execution goes against the grain. If Susini’s production is tracked by his labor and technical acuity rather than the designs he created, how and where do we locate him today? Indeed, in the case of Susini, both an assimilable hand and anonymous execution suggest an artist that is simultaneously present and absent. How does framing Susini’s position as an “invisible technician,” or even “alter-ego,” for example, open onto new ways of studying assistants as vital fabricators and recuperating these makers’ nebulous positions between design and artifact?7 That is, how can the study of sculpture favor techniques “from below”? To tell the story of Susini as both independent laborer and cooperative assistant is to recuperate from the extant objects an otherwise absent or forgotten historical record. It is to grapple with invisibility as a necessary hurdle and charged heuristic.

Over the past eight months, I have explored how strategies in data curation and imaging technologies can, literally and metaphorically, help visualize these historical gaps. At the same time, I have apprenticed as a fabricator working with local foundries to understand the intricacies of casting, from wax to bronze, and to familiarize myself with Susini’s embodied experience as a sculptor. In what follows, I share some early notes on what I have learned. First, I will consider how amassing and sorting art objects as data points can reveal unnoticed patterns and trends. Then, I will introduce my own experiments in wax modeling and casting. Putting oneself in the artist’s shoes can not only fill the gaps in what we can know, but also complement digital reconstructions through an experiential and artifactual approach. Finally, I will share my preliminary experiments in 3D imaging compared to photogrammetry, highlighting the challenges of using 3D scanning to capture reflective surfaces like bronze. Here, I will consider 3D scanning as its own form of casting. Throughout, I wish to linger on the potential of seeing and using these technologies as surrogates for the historical process or object they themselves try to capture.

Objects as Data

Of the words associated with the Renaissance bronze statuette, “reproduction” is perhaps the most fitting. All bronze casts are, by definition, reproductions of an earlier model made in wax; many are reproductions of other sculptures, large or small; and some are even reproductions of yet other casts. Whereas in the modern age ideas of replication or reproducibility often carry with them connotations of the copy or even the derivative, the very technology of casting is imbricated in the rhetoric of reproduction.

Reconstructing the object—as would the caster himself.

Let’s begin with a brief overview of the process and terms involved: In what is often referred to as “direct casting,” the process begins with a model in wax around which an “investment” in clay or plaster is built. The wax is then “burnt” (melted) out, and into the cavity molten metal is poured—this will become the finished cast. Important here is that the original model is destroyed, and a unique cast produced. In “indirect casting,” we begin with a model in any material (clay, wood, even metal) from which a “piece-mold” is made, a type of mold deconstructed in pieces so as not to damage the object it replicates. This piece-mold can then be used and reused to make multiple copies in wax, which are then cast in metal using the direct method above. Multiple versions of the same model can be produced in this way.

In the sixteenth century, in and around the Giambologna workshop, the use of indirect casting and a demanding art market meant an increase in the production of small bronzes. Giambologna employed, in addition to Susini, several other artists who were responsible for adapting and reproducing his designs. The great number of casts produced during these decades has fueled debates about authorship and dating, but also complicated attempts to assign and differentiate Susini’s output. Exhibition catalogs exacerbate the issue, arbitrarily assigning or even muting his involvement. And yet, a study of Susini’s practice cannot begin without a catalog of what he produced. The large number of works in his orbit, moreover, presents an extraordinary amount of raw data in need of explanation. In this pursuit, I turned to a simple spreadsheet. More than a list of the works to which Susini is attached, this document is a repository of each object’s history with technical data describing their size, weight, and other characteristics. While the genre of “catalog” in art history is a mode of collation and explanation, this repository functions equally as an interactive database for sorting and (re)categorizing the objects.

| Unique ID | Location Known? (Y/N) | Location | Accession # | Title | Subject | Model | Length (cm) | Width (cm) | Height (cm) | Period | Start Date | End Date | Attributed Certainty “Score” | Author/Artist | Founder | Collaborators? | Signature | Contested? | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 241021-043 | N | Private Collection | The Flying Mercury | flying Mercury | 17.4 | late sixteenth century | 1575 | 1600 | model by Willem Danielsz van Tetrode | Antonio Susini? | Avery, Giambologna, 1998 | ||||||||

| 2 | 241021-006 | N | Private Collection | Mercury in Flight | flying Mercury | 64.8 | late sixteenth century | 1575 | 1600 | model by Giambologna | Antonio Susini? | Avery, Giambologna, 1998 | ||||||||

| 3 | 241021-012 | Y | J. Paul Getty Museum | 94.SB.11.1 | Lion Attacking a Horse | Lion Attacking a Horse Type 1 | M-01 | 24 | 28 | first quarter 17th century | 1600 | 1625 | Antonio Susini | or Giovanni Francesco Susini | ||||||

| 4 | 241021-032 | Y | Detroit Institute of Arts | 25.20 | Lion Attacking a Horse | Lion Attacking a Horse Type 1 | M-02 | 25.4 | 30.5 | 1580-90 | 1580 | 1590 | Antonio Susini | ANTo. SVSINI | FLORE. OPVS. | ||||||

| 5 | 241021-021 | Y | Kunshistorisches Museum, Vienna | Kunstkammer, 6018 | Lion Attacking a Horse | Lion Attacking a Horse Type 2 | M-03 | 38 | 26.5 | 33 | ca. 1600 | 1590 | 1610 | Antonio Susini | ||||||

| 6 | 241021-014 | Y | Kunshistorisches Museum, Vienna | Kunstkammer, 5893 | Venus Urania or Allegory of Astronomy | 38.8 | c. 1575 | 1565 | 1585 | Giambologna | Antonio Susini? | Antonio Susini | GIO BOLONGE | |||||||

| 7 | 241021-026 | Y | Galleria Borghese | CCXLIX | Farnese Bull | Farnese Bull (after the antique) | 48 | 1613 | 10 | Anonio Susini | ANT.II SUSINII FLOR.I: OPUS/ A D MDCXIII | N |

In addition to standard metadata like “artist,” “collection,” and “date,” each object also has a unique identification number (i.e. 241021-006, labeled according to date and order of entry), through which objects of similar subjects can be grouped and “certainty” of authorship mapped. Casts signed and dated by Susini, for example, receive a “certainty” score of a 9 or 10, whereas others more tenuously designated in early catalogs as “possibly cast by” receive a much lower number.8

Figure 3. (Left) Antonio Susini. A Pacing Horse, ca. 1600, bronze, 29.5 x 32.35 x 9.5cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, A.11-1924. Signed ANT: SVSINII FLOR: FE. (Right) Giovanni Bologna, called Giambologna, Walking Horse with Hogged Mane and Saddlecloth Bearing the Vinta Coat of Arms, ca. 1610, bronze, 27.5 x 8.9 x 25.1 cm. Clark Art Institute, 1955.1004. Image courtesy of Clark Art Institute.

Most exciting here is the category of “model,” an auxiliary sheet that seeks to track and recuperate how many models—many of the same subject—Susini was working from. Often designated in catalogs generally as “Cristo Morto [crucifix] Type A” or “Cristo Morto Type B,” to account for deviations in design, for example, the number and type of models used have yet to be comprehensively mapped. Though a few waxes and terracottas from the Giambologna workshop survive, the majority of models are long gone, either destroyed in the workshop or lost. To reconstruct their movement and lifespan from the extant casts is to visualize the otherwise intangible.

This database is in an early stage of development and much work remains to be done to reap significant conclusions; an expanded version, for example, might include all of Susini’s colleagues in the Giambologna workshop to more definitively understand the rate at which models were circulated and reproduced between them and where the derivations lie. Artists moved from model, to wax, to bronze. My data sculpts in reverse, moving from bronze cast, to maker, and eventually, to the lost model.

Objects in Process

Describing the production of molds for casting in bronze, Sienese metallurgist Vannoccio Biringuccio advised his reader, “If you have not been the workman yourself, you must at least have been an active helper in this and in every other part in order to be able to follow everything without a fault.”9 Still today Biringuccio’s provocation rings true: you won’t properly understand how something is done until you have tried it yourself. In the world of artistic technique and process, this is especially apt. If Susini’s expertise lay in both ephemeral techniques and surface treatment, the only way to understand his labor, at least in part, is to reconstruct it oneself. As a trained painter, I am very familiar with this idea; but having more limited experience sculpting or casting, I entered a novice.

You won’t properly understand how something is done until you have tried it yourself.

In about 1596, Susini modeled and cast a series of bronze statuettes for the tabernacle of a Carthusian monastery (the Certosa) outside Florence, the production of which is among his most documented in both period sources and museum conservation. Of these figures, Saint Matthew, now conserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, seemed a good subject to experiment with. The process began with a fundamental question that Susini and other artists tasked with reproducing, reducing, or enlarging a sculpture would have faced: How does one render something to scale? Not having the original readily available to measure and compare, I instead turned to the two dimensional and worked off scaled photographs of the sculpture from various angles. To simulate in modern, quicker means the Renaissance piece-mold, I made a rubber mold of my clay (itself a “free copy” destroyed in the molding process) to cast a wax replica.

Figure 4. (Left) Antonio Susini (model and cast, possibly after a model by Giambologna), Saint Matthew, 1596, bronze. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1957, 57.136.2. Scaled by author. (Right) Half of the rubber mold to cast my free copy in wax.

The cast wax is malleable with heated metal tools and an open flame, but it requires a gentle touch. Initially I assumed the wax was a quick, auxiliary step—a means to a bronze end. In reality it is both time-consuming and labor-intensive. In a task of repair and editing the wax modeler is as much sculptor as he is “fixer.” Indeed, one wants the finished wax to be as close to the final product as it can, for it is much easier to alter in soft wax than in hard, obdurate metal.

The wax is prepared with vents and sprues that are burnt out, leaving behind intricate channels for the molten bronze to properly fill.

Preparing the wax to be cast requires focus of another kind. Maintaining the structure of the wax and ensuring it will be properly cast becomes the priority. The wax is prepared with vents and sprues that are burnt out, leaving behind intricate channels for the molten bronze to properly fill. An imprecise alignment of vents means a potentially faulty cast. Modern casting no longer uses the investment technique, but instead what is called “shell casting,” where the wax is repeatedly dipped in a ceramic shell slurry and sand. Once cast, the real work begins. The bronze must be excavated from the shell (no easy task), the core removed, and the sprues and vents cut off, all before the polishing and chasing of the work can even begin.

Figure 5. (Left) My cast of an antique torso mid-removal from its investment. (Right) Same cast illustrating the vents, sprues, and cup (once wax, now bronze).Courtesy of author.

Sanding, polishing, and engraving the bronze surface is a long process, one I have only just begun. But for me there is one striking takeaway: the finishing process is one of reversal, trying to erase all signs of the process and grime that came before—that is, removing the debris from casting and filling all holes, seams, and repairs. The quality of the surface and gestures involved—high polish and intricate design—instead replaces these intermediary processes as signifiers of the artist’s labor. For the artist or technician, this is significant: in order to achieve the height of their craft, they must erase all traces of their labor.

Objects as Surface

As we have seen, cleaning and finishing a bronze cast is—and was—a labor-intensive process preoccupied with surface. Whether working in bronze or pixels, to cast is, after all, to capture surface. In this final section, I want to discuss another means by which to “cast” a bronze object: 3D scanning and photogrammetry. Increasingly in the humanities, 3D imaging technologies have been integrated to conserve and closely study historical objects otherwise inaccessible or ill-preserved. These technologies are particularly useful in revealing technical data about an object and have been integrated most successfully into conservation studies. Not only do they have the potential to offer refined images of an object’s surface geometry, for example, but they also capture its exact dimensions. My interest in the technology began out of its potential for the latter.10

The characteristics that defined bronze—shiny, polished, reflective—made it resist reproduction, the very process to which it is indebted.

The Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) owns a gilt bronze corpus for a crucifix originating from or around the workshop of Susini, one of many attributed to the artist. Ultimately, the objective is to scan two of these and compare the 3D models to determine where, if at all, piece-molds were reused or altered. Though measurements can be taken manually from an object, they are inexact for curved surfaces in particular. Still in the early stages of this endeavor, I have been experimenting with the technologies available and the involved logistics of handling and imaging a sixteenth-century museum artifact. A series of test objects—some produced during my casting project—reveals the potentials and limits of doing so, and a preliminary photogrammetric model provides a standard on which to build.

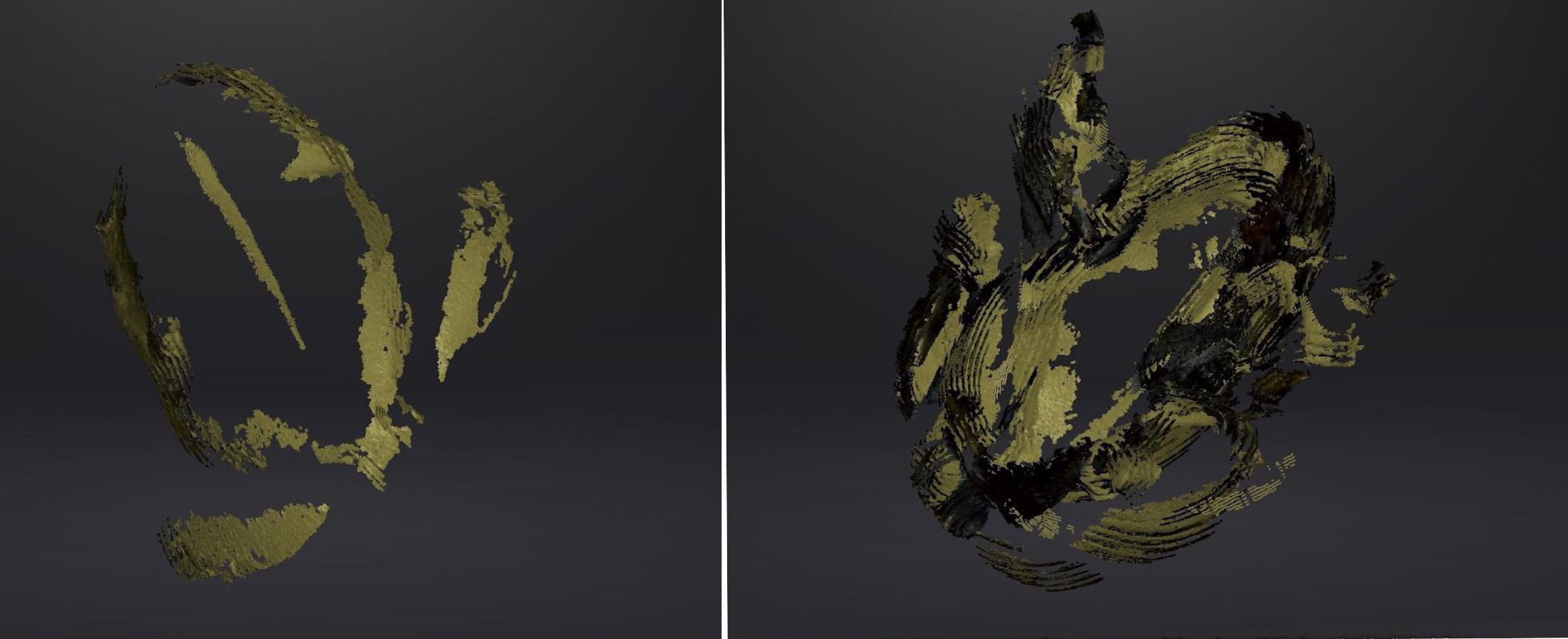

The first few scans of a small brass frog with a tabletop scanner (EinScan SP) made it clear the process would not be straightforward. Very little data was captured in these initial scans and only in areas where the patina was darker and matte.

Figure 6. My initial—unsuccessful—scans of the brass frog.Courtesy of author.

The reflective surface of the metal was simply not captured by the scanner. For a project centered on bronze, this was a problem. In such cases, there is a matte, white spray used to cover objects so that they register more readily in the scanner’s camera. This solution was not viable, however, when working with invaluable museum objects. There was a special irony to this hurdle. The characteristics that defined bronze—shiny, polished, reflective—made it resist reproduction, the very process to which it is indebted. In a project defined by its desire to recuperate a “hidden Susini,” the fundamental work and gestures he was responsible for would be rendered, quite literally, invisible.

Naturally matte materials, like clay, or, on the other hand, semi-gloss, like wax, translated well to a 3D scan. I used both my wax model and fragments from my original clay model to test out the level of detail and structure picked up. Where the brass result was piecemeal at best, even from an initial scan of the clay the tabletop scanner was able to produce a far more cohesive and legible model.11 For the wax, which exceeded in height the limit of the tabletop scanner, a handheld version (Einstar) was used.

Figure 7. (Left) 3D scan of terracotta clay drapery fragment (EinScan SP, tabletop). (Right) 3D scan of wax model (Einstar, handheld).Courtesy of author.

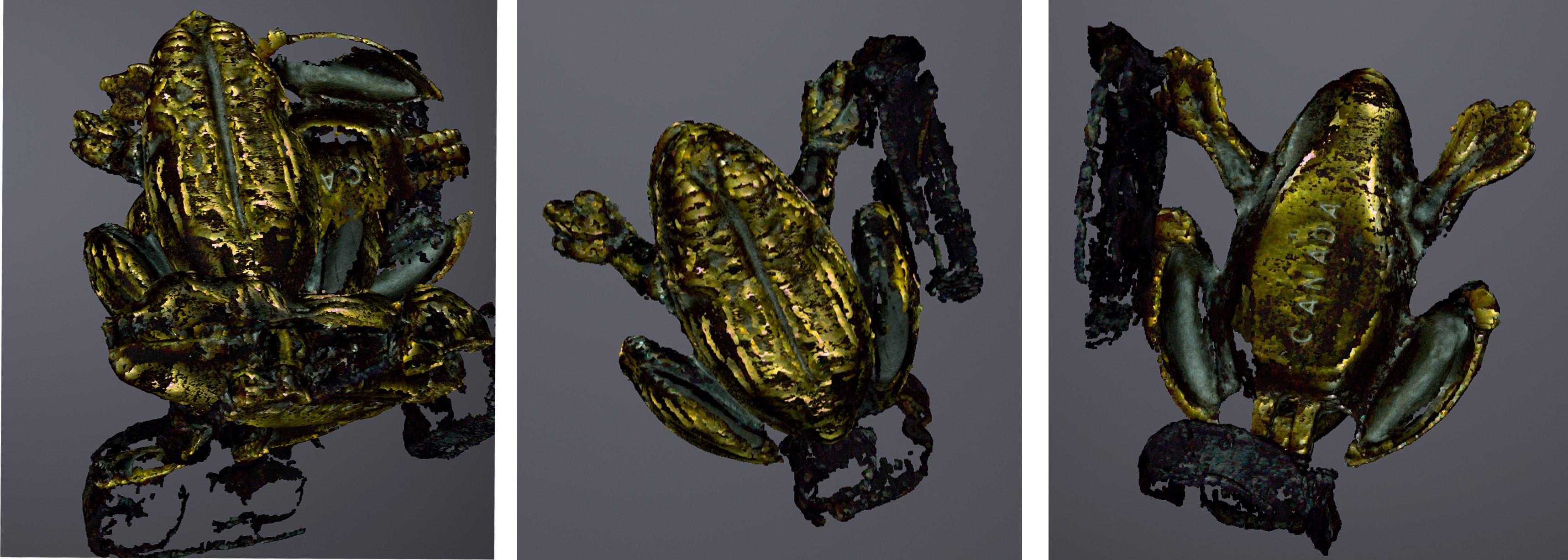

In both, the technology shined and produced the sort of results I was hoping for; the only problem was that those results were with the wrong materials. If the object’s reflectivity was the dominant issue and not the technology, then the object’s refraction needed to be mitigated. One option was to limit the light source (shades and overhead lights), but the scan was only marginally better. However, it was quickly realized that it was not only the position and strength of the light source that mattered, but also the orientation of the object. Instead of positioning the frog flat on its base, two orientations on its side, horizontal and vertical, were tried, securing it with a bit of casting wax (something with enough tensile strength to keep the frog vertical but not enough to obscure the object itself). These changes garnered shockingly better results, and each orientation captured slightly different data. Not only did the scans now capture the contours of the object in full but, when multiple scans were aggregated, they even captured and reproduced the reflective surface of the brass itself.12

Figure 8. (Left) Illustration showing number of scans and variety of orientation that were aggregated. (Center) Combined scan of brass frog, view from the top. (Right) Combined scan of brass frog, view from the bottom.

In 3D scanning, it is necessary to “mesh” the model, which effectively fills in the data gaps and together renders a more lifelike scan.13 If the raw scans can be seen as a hollow, untreated bronze cast—with imperfections, sprue holes, and other proverbial “casting flaws”—the mesh function becomes a surrogate for the finishing processes of polish and repair. The results of the mesh were striking, if also unexpected.

On the one hand, the surface is surprisingly reflective, reading without doubt as metallic material. On the other, however, it is dark and the details blurry, two characteristics that didn’t come to define the aggregative scan from which we started. Where both finishing stages in bronze and 3D scanning brought out the polish, in bronze the details are also defined; here, in pixels, they are obfuscated. Post-processing in EinScan and Rhino did little to remedy these effects, and more experimentation is needed. Nevertheless, the reflectivity of the material interfered with not only the laser scan itself, but also the post-processing—only in the inverse: whereas the laser scan was at first unable to pick up highlights, the mesh processing centered on the reflective, thus negating, in turn, all other surface textures.

To cast is, after all, to capture surface.

In addition to 3D scanning, which uses laser measurements, photogrammetry uses photographs to build the model. Whereas scanning is more accurate in shape and color, photogrammetry offers better color and surface texture. To test the potential of this technology, I used Metascan Pro to create a model of a bronze that I had just recently cast and removed from its investment. The cast had yet to be fully cleaned and polished and as such displayed a number of surfaces, from rough to polished bronze: perfect for testing photogrammetry’s ability to handle a variety of surfaces, reflective or otherwise. I made a model using two hundred photographs of the cast. Though there are some losses and peculiarities, the result captures the surface in relatively high detail and documents the dimensions with some accuracy. (It was about half an inch off in all directions, which could have been due to a skewed angle of the camera, for example.) The two polished areas on the back of the cast (where the vents had been cut) are picked up without difficulty and read in equal detail to their rougher counterparts. A three-part comparison between stills from the photogrammetric model, the 3D scan (using the handheld Einstar), and a photograph illustrates some of the differences between technologies.

Figure 10. (Left) Still from 3D scan, Einstar handheld. (Center) Still from photogrammetry model. (Right) Still photo of cast.

Most notably, the 3D scan is unfocused, and the surface textures read more or less homogenous; the photogrammetric still, on the other hand, perhaps expectedly, reads closer to that of the still photograph.

Now we can return to Susini and the PUAM Cristo Morto. Though at this time I was not able to take photogrammetric scans of the object directly using the Metascan Pro phone application, I was able to do the next best thing. Using Metascan’s online platform, I uploaded three hundred photos of the object from all angles that I had taken during a study visit last November; from these images, it generated a relatively successful model.

Some areas are slightly less focused and the hands, in particular, are not well rendered.14 Despite this, the measurements are more or less commensurate with those I had taken in person, suggesting that the distortion of the object was not as great as expected. The surface texture and color are somewhat muted in this model, coming off closer to an ochre color than reflective gold, as it appears in person. Despite these inconsistencies between model and object, the model still offers a vivid, interactive view of the object’s technical intricacies and state of conservation—its chased surface, patchy gilding, visible plugs and repairs—in three dimensions.15 Whereas the conditions of the tabletop scanner are better controlled—the object is a consistent distance from the camera—photogrammetry is a bit harder to regulate and more prone to human error. A dual-approach combining both 3D scanning and photogrammetry (one prioritizing shape, the other surface) would instead be optimal. I will continue to experiment with this combined approach by reconstructing the object—as would the caster himself—from the bottom up, giving both surface and structure equal regard.

Recently, art historian Michael Cole published an article in West 86th entitled “Bronze as Model.”16 In it, he suggests how the genre of Renaissance bronze statuette, commonly seen as a reduction or copy in itself, may have inspired the production of subsequent artworks—as copies, enlargements, or, even entirely new subjects. In the approaches explored above, the small-scale bronze indeed becomes the model from which we must extract—and in some ways critically fabulate—otherwise invisible narratives of production. The end result for the artist and workshop is the beginning from which we—as historians, practitioners, and data wranglers—must learn to cast in reverse.

O. Doering, Des Augsburger Patriciers Philipp Hainhofer Beziehung zum Herzog Philipp II. von Pommern-Stettin - Correspondenzen aus den Jahren 1610– 1619 (Vienna, 1894), 97: “Li seguenti 10. Pezzi di bronzo sono tutti di mano del E.mo S.r Cav. Gio. Bologna, di gloriosa memoria, con somma dilignza inventati, et ciaschuno è sopra un basamento posto . . . un gruppo d’un lione, ch’amazza un cavallo./un gruppo d’un lione, ch’uccide un toro.” ↩︎

Filippo Baldinucci, “Notizie di Giovanni Bologna,” in Notizie De' Professori Del Disegno Da Cimabue: In Qua, Per Le Quali Si Dimostra Come, e Per Chi Le Bell' Arti Di Pittura, Scultura, e Architettura Lasciata La Rozzezza Delle Maniere Greca, e Gottica, Si Siano In Questi Secoli Ridotte All' Antica Loro Perfezione (Firenze, 1846), 2: 583. ↩︎

The inscriptions, as quoted in text, relate to the Roman casts. There is slight variation in the Louvre and DIA versions: the Louvre inscription reads “ANT-/SVSI/NI.F.,” and the DIA, “ANT.O SVSINI FLORE. OPVS.” ↩︎

For matters of space and clarity, this is of course a simplification of ongoing discussions and debates surrounding these works and their authorship. For a more comprehensive account, see Peggy Fogelman’s catalog entry for the Getty’s (unsigned) pair. Peggy Fogelman, “Lion Attacking a Horse and Lion Attacking a Bull,” In Italian and Spanish Sculpture: Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection, edited by Peggy Fogelman et al. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002), 177–89. ↩︎

James Holderbaum, The Sculptor Giovanni Bologna (New York: Garland, 1983), 255; Katherine Watson, Pietro Tacca, Successor to Giovanni Bologna (New York: Garland, 1983), 47. ↩︎

In a letter from Giambologna to Belisario Vinta, August 6, 1605. Cited in Watson, Pietro Tacca, 33n37. ↩︎

For these concepts, see Steven Shapin, “The Invisible Technician,” American Scientist 77, no. 6 (1989): 554–63; Jacques de Caso, “Serial Sculpture in Nineteenth-Century France,” in Metamorphoses in Nineteenth-Century Sculpture, ed. Jeanne L. Wasserman (Cambridge, MA: Fogg Museum, 1975), 1–28. ↩︎

It should be acknowledged, of course, that signatures, especially those in bronze, do not in and of themselves assert authorship with absolute certainty. For our purposes, however, they offer measures from which to work. ↩︎

Vannoccio Biringuccio, The Pirotechnia of Vannoccio Biringuccio, trans. Cyril Stanley Smith and Maratha Teach Gnudi (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1966), 220. ↩︎

I am also inspired here by other sculpture 3D-modeling initiatives in art history, such as the collaborative multidisciplinary project, “The Technical Study of Bernini’s Bronzes,” between the University of Toronto, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the Getty Research Institute. https://www.berninisbronzes.com/ ↩︎

Prior to this I had tried the handheld scanner. Surprisingly, this scanner picked up little to no data. It is my sense that the handheld scanner is most effective for large-scale objects. ↩︎

I took a number of scans but aggregated six of the best and fullest for the model reproduced here. ↩︎

A “watertight” mesh fills any openings in the model (ideal for 3D printing), while a “nonwatertight” model follows only the contours of the raw scans and leaves gaps where there is missing data. Luckily, enough data was gathered in these scans that both renders were quite similar. I used the watertight option for the model reproduced here. ↩︎

Photos of either higher quality or focus might remedy these imperfections, as it appears the photogrammetry software was unable to differentiate the contours of the fingers from the background underneath. ↩︎

I took the photogrammetry model’s measurements using Metascan. While the proportions were similar, Metascan is peculiarly measuring at 10x magnification, labeling the object’s five-centimeter forearm, for example, as fifty. ↩︎

Michael Cole, “Bronze as Model,” West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 28, no. 2 ( 2021): 232–39, https://doi.org/10.1086/721203. ↩︎